A story by filmmaker Rebecca Miller

I discovered the Flaherty film in the fall of 1976 when I was 20 years old and a third-year student at Rhode Island School of Design, enrolled in the film program. Early on I learned to edit film, a skill I seemed able to master, but by the time I graduated I had very little hands-on experience. I had spent much of my time reading books about filmmakers and had majored in filmmaking as I wanted to be engaged with ideas.

In the fall of 1976, I was reading this book about the documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty called The Innocent Eye, by Arthur Calder-Marshall. I found this passage that said:

“Another little assignment was the shooting in 1945 of footage at the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design about the John Howard Benson technique of calligraphy. It never came to anything as a viewable film. Benson and Flaherty did not get on.”

I went off to the RISD museum the next day and asked if anyone knew anything about the project. No one seemed to have any idea that this had ever existed. But they said, “Let’s look in the attic.” And there in the big dark space, among the broken colonial chairs, and the empty gold frames, was a stack of film cans--they said FLAHERTY. There it was, the film from the Benson project.

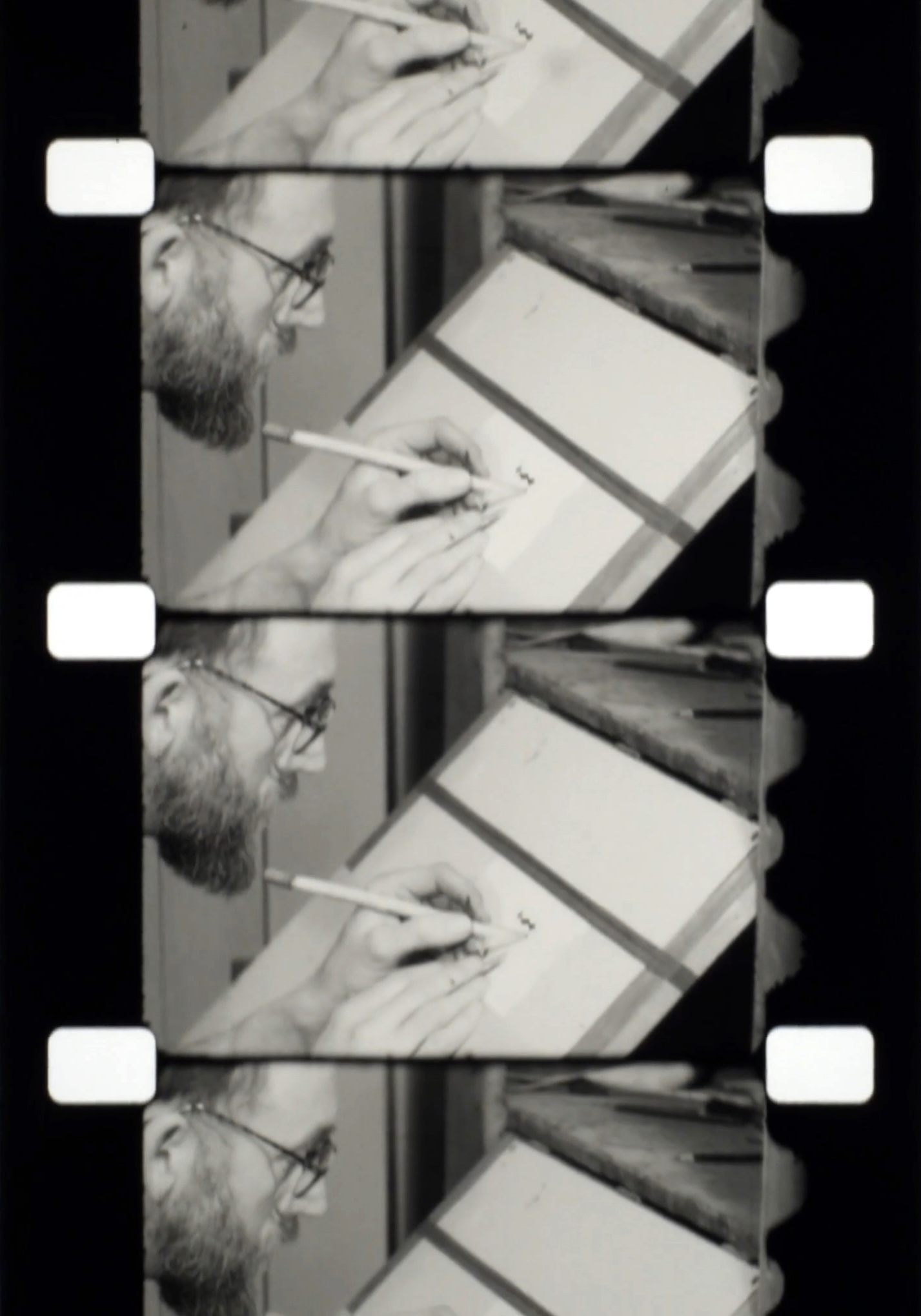

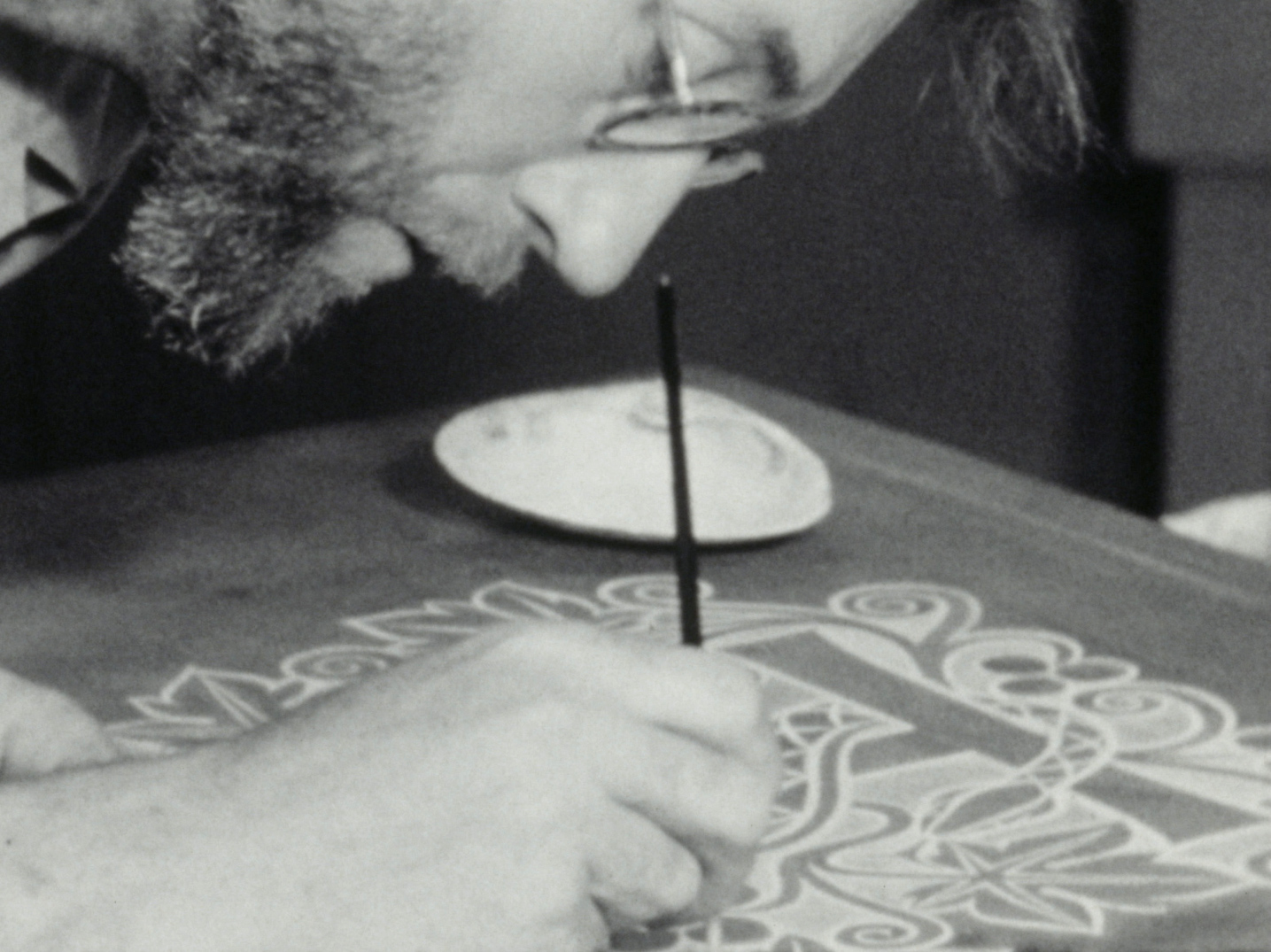

We had the cans of footage transferred to the RISD film department to be reviewed. The material was in terrible shape and badly scratched. I was being very careful and always wore white editing gloves. The film was disorganized mess. Some of it tightly rolled up as if on your finger, and it appeared to be edited by an amateur. It was difficult to tell if I was working with the original 16mm reversal stock or workprint. It had no labels.

The footage was recorded largely in black and white 16mm reversal stock. A few scenes were shot in color, but I have doubts they were from Flaherty. Most footage was shot in the summer of 1944. Additional production was likely in 1945 and two production dates were added in 1946 with Richard Leacock in the crew.

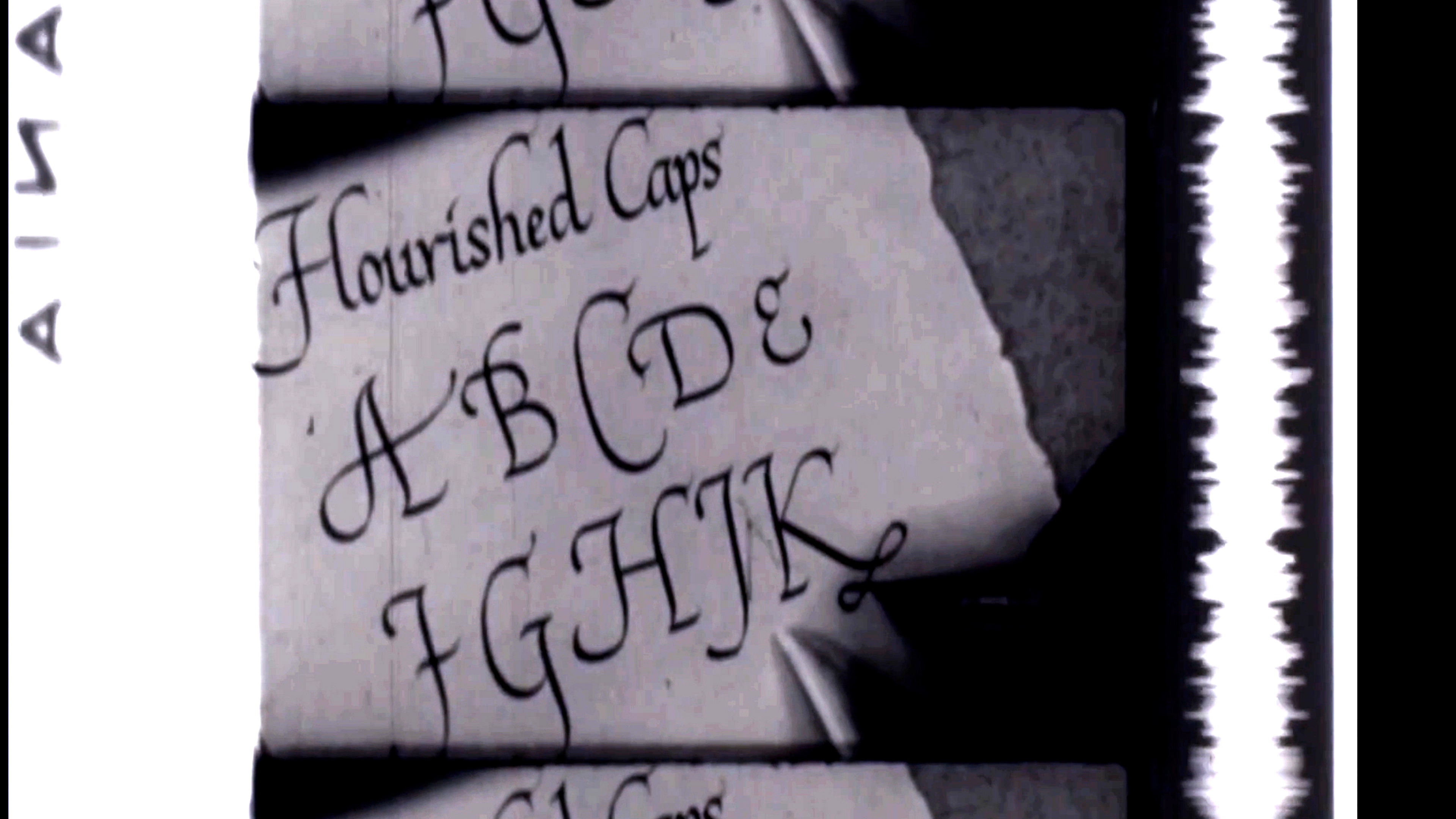

The footage that exists in color, mostly of densely detailed calligraphic writing, does not look like it came from Flaherty's hand and why would Flaherty add color footage to the project? Did Benson hire another photographer? Seems unlikely, but possible. One of Benson's typewritten notes suggests he wondered about the implication of bringing in another photographer.

During these years at RISD when I was working on the Flaherty-Benson project I dreamed about having a faculty member take me under their wing and guide me. I had no idea how to gather research, had no experience as a historian, and wished I had someone with whom I could have a regular check-in and give them updates. “Hey, I found this great letter!” I was overwhelmed by the project, thousands of feet of film and hundreds of letters of correspondence. I spent almost two years, sitting in my Benefit Street studio apartment with my cat Frankie, typing up chunks of text and organizing all of it on a big bulletin board. I was a determined writer, but I lacked focus and good executive function. There was no one in the film department remotely interested in the task of guiding me through the project.

Finally, art historian, Baruch D. Kirschenbaum, PhD, who was the head of the Liberal Arts Department, gave me the guidance I needed. He was a formidable guy who struck fear in the hearts of many a RISD student. Smoking cigarettes together in his office on late afternoons, we reviewed my thesis page by page, and he gave me valuable writing points and organizing tasks. He saved me, really, and I owe him a great deal for his help with the project.

I gave up smoking in 1980.

The interviews conducted in 1976.

I worked up my courage and started calling people involved with the project. Everyone was very, very nice and I took my cassette recorder and recorded interviews on tape with Mrs. John Howard Benson, in Newport, Gordon Washburn, in New York, and Richard Leacock, on the faculty at MIT in Cambridge, MA. I also met Dan Jones, a friend of Benson’s for lunch, after I got lost on the bus on my way to Newport.

In New York, I got to know filmmaker Willard Van Dyke, who knew Flaherty well, and his wonderful wife Barbara Van Dyke, who ran the Flaherty Seminars. They were very interested in the project and viewed my rough cut in the spring of 1978. Also, people at Film Comment Magazine, the Museum of Modern Art, and many others I met along the way. I also visited the Flaherty farm in Vermont as a guest of his daughter Monica Flaherty Frassetto.

Listening now to the interviews on cassettes, at myself as an inexperienced 20-year-old student, is a cringe-worthy experience. I hear the tick-tock of the clock in Washburn’s apartment, the side conversations Leacock had with students, and Mrs. Benson asking me to turn off the recorder because she didn’t want to be recorded saying anything that may not be considered very nice. Beyond the distractions, many valuable things were said. And since the interviews conducted on cassette tape were more casual and often ran more than an hour, real gems came out of the conversations--many more than were recorded on 16mm over a year later.

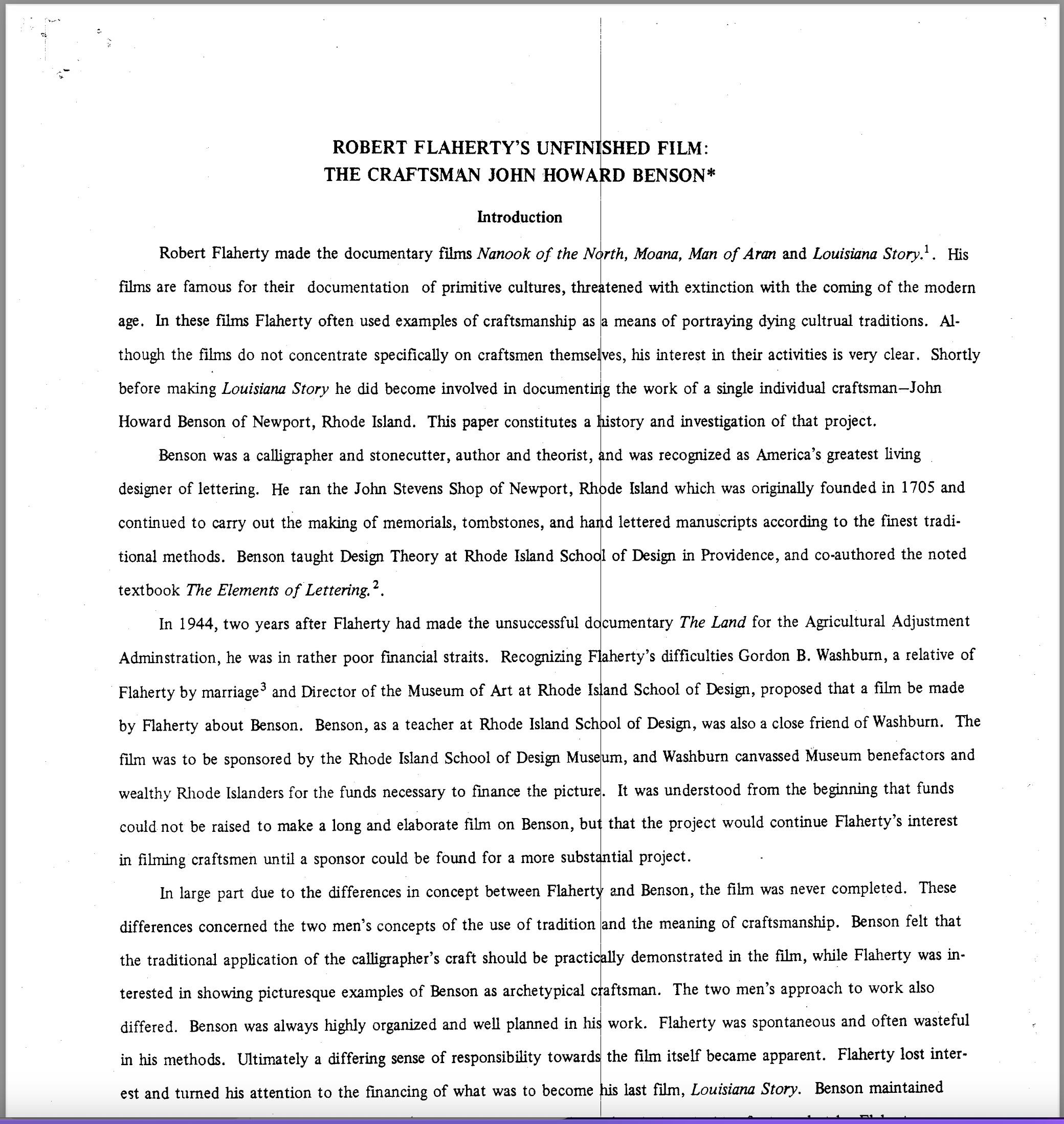

ROBERT FLAHERTY’S UNFINISHED FILM: THE CRAFTSMAN JOHN HOWARD BENSON is the most comprehensive history about the Benson project written to date. It was finished in 1978, while I was a senior at RISD, and submitted as my senior thesis. The report contains extensive quotes from the interviews conducted and the correspondence gathered during my two years of work on the project. I had hoped that the report would be published in a magazine like Film Comment, but the piece was rejected. I had no experience as a published writer. Reading back on this work I finished over 45 years ago, I’m surprised at the depth and quality of the report.

“The collaboration between Robert Flaherty and John Howard Benson ended with the stonecutter having the last word. If Benson’s design decisions did not dictate Flaherty’s actions during his life, they did oversee him after his death.”

Note: In 1979, I hired a typist to clean up my messy typing and give it a professional look. This is why the report has a date of 1979, though it was completed in 1978.

When the auteur theory was introduced into film criticism in the 1950’s and 1960’s, critics began to judge films not for the own merits necessarily, but for the significance in the careers of the directors. This new critical direction presented the history of cinema by mapping out the great directorial forces—Griffith, Renoir, Hawks, Ford, Flaherty—and traced their development from movie to movie—statement to statement. This approach justifies all of a director’s works whether or not in the end they be judged significant in themselves. The Benson project and resultant footage, where it did not result in one of Flaherty’s masterpieces like Nanook of the North or Louisiana Story, becomes important, then, as part of his career. Long forgotten in the biographies of Flaherty, the Benson material reveals important aspects of Flaherty as filmmaker and artist. None of the usual methods for studying film can be used with this material because no evaluation about direction, editing, script, narration or music can be attempted. Decisions on these matters were either never made or made by others, including Benson himself.

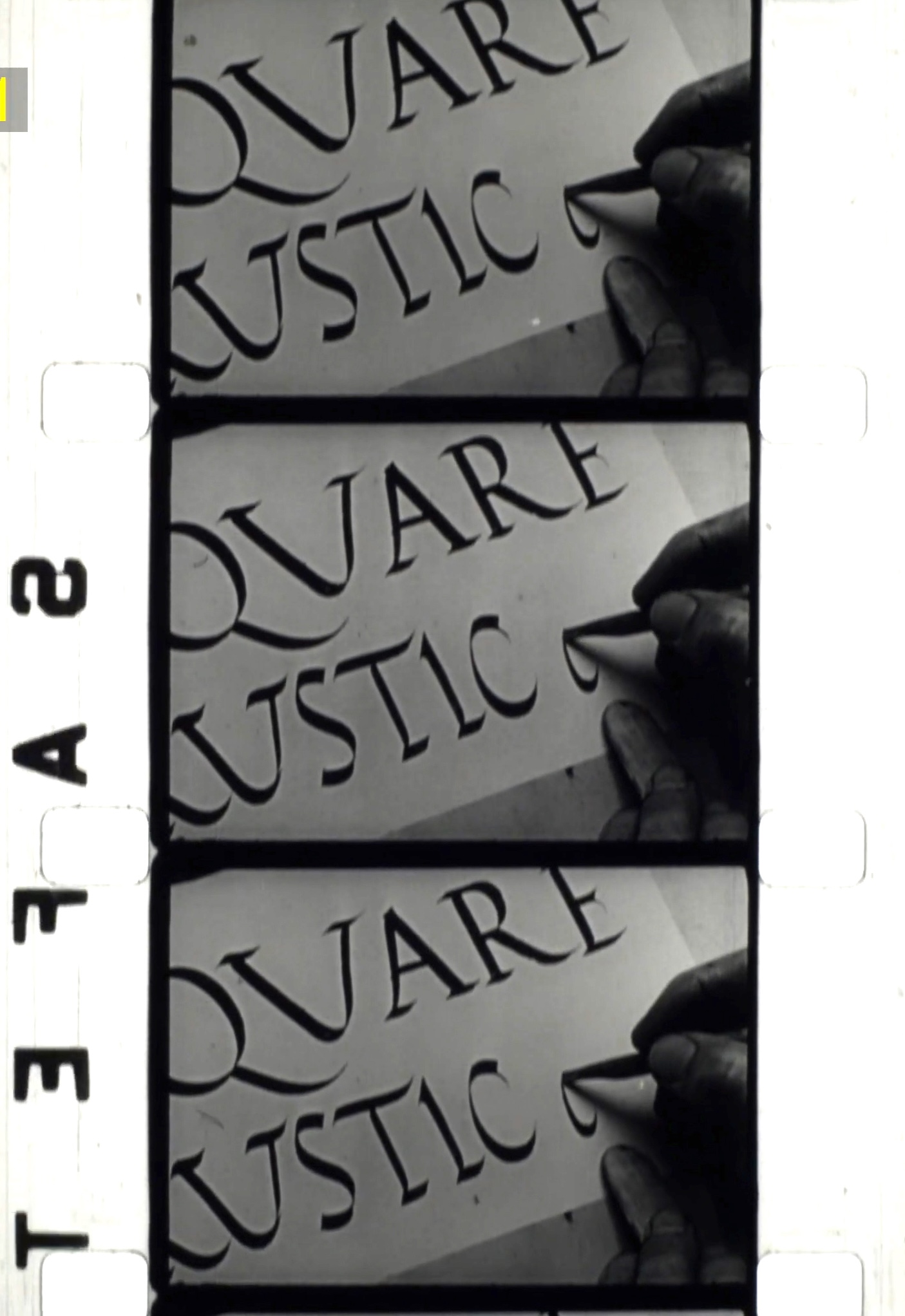

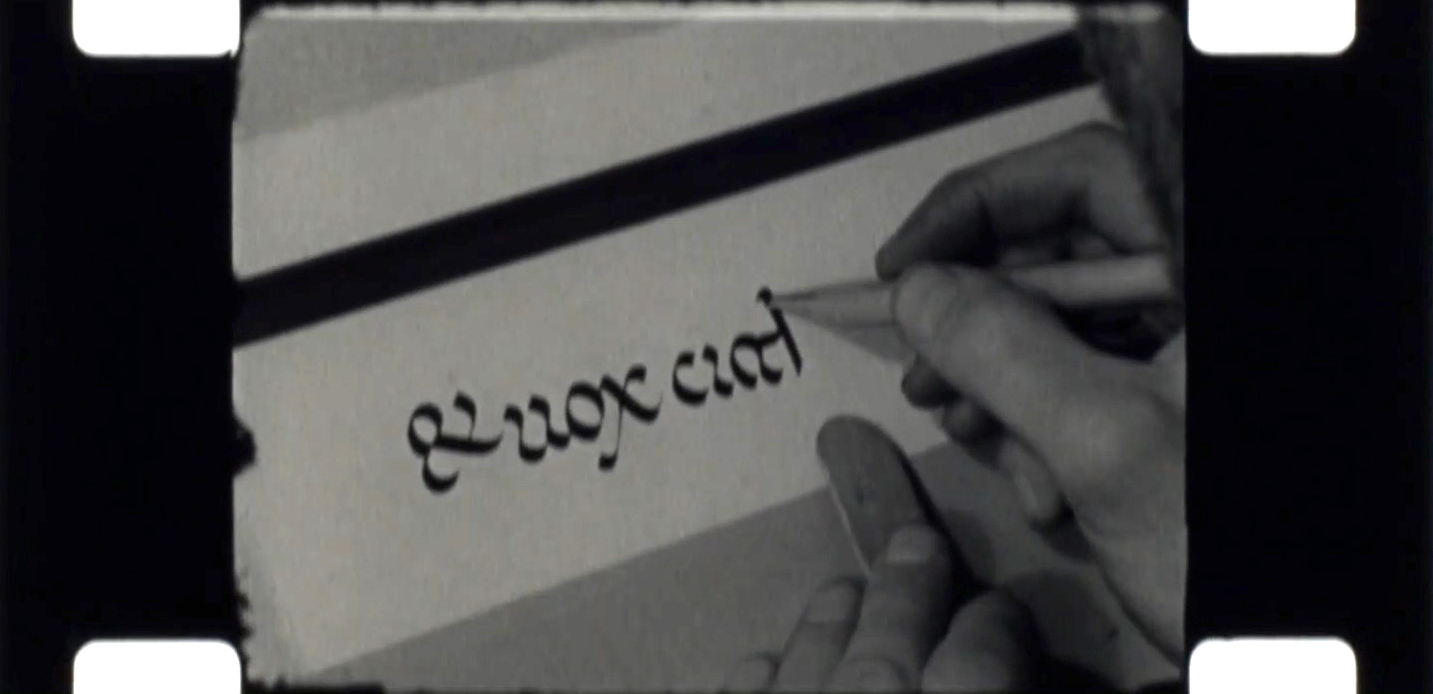

The whole Benson project demonstrates Flaherty’s cinematic range and focuses in on his particular interest in crafts and craftsmen.

A study of the fragment can also reveal some of the aspect present in his more important, completed works. On another level, the material is noteworthy because it displays the extraordinary range of Benson as man and artist. It demonstrates his skills as master craftsman performing as stonecutter and calligrapher and gives graphic illustration to his theories about the superiority of traditional forms and materials and their role in good design.

The whole history of the project reveals the interaction of two distinct and very different artistic temperaments working in troubled collaboration.

The history of the film is derived from three bodies of documentation: the over 15,000 feet of existing Flaherty film (8,700 feet of black and white 16mm reversal stock and over 6,300 feet of the film in various stages of editing and prints); over 800 pieces of correspondence between persons involved in the production; and interviews conducted with Mrs. John Howard Benson, Richard Leacock, (Flaherty’s cameraman on Louisiana Story) and Gordon B Washburn. Secondary material is derived from the general Flaherty and Benson bibliographies.

When I graduated from RISD in 1978 I couldn’t wait to get this project off my desk.

I had spent two precious years of my college life engaged in something that I felt was important, but I had not completed my 16mm film, and I graduated with little hands-on experience. My big thesis? No one seemed to care. Who goes to RISD to write?

I had landed a job working as an editor at WJAR-TV 10, the local NBC station in Providence. This job, which started the day after graduation, made me feel very ready to move onto a career in film, television, cinema, or something else. Jobs were hard to find, and even though I was paid around $7,000 a year for the job (not including what I was to owe in union dues), this finally felt like success. Hey, none of my pals in the film department went off to a job in television. Big time, here I come, (yeah, right...)

I packed up the precious Flaherty footage and gave it back to the museum. I then packed up my research elements—the books of correspondence, cassettes, ¼” tapes, my 16mm film reels, and my thesis into a cardboard box. I then dragged the box around as I moved from Providence, R.I., to Brookline, MA, to West Hollywood, CA, back to Brookline, to Newton, MA, and on and on for 37 years. I never once opened the box. Finally, in 2015, I contacted the school and asked them if they were interested in my elements? They drove up and took my box, promised to place them next to the Flaherty materials, and thanked me for my gift with a nice letter. What a relief. Finally, this project was off my chest and out of my life.

That is until I received an email from Margot McIlwain Nishimura, the Dean of Libraries at RISD. She and Regina Longo, on the faculty at Brown University, were teaching a class in film research and preservation and wanted to use my Flaherty materials in the class. Really? I was so surprised by the renewed interest from the faculty and the students too. They asked me to come and meet with the class and I had a great time telling my story to the students and everyone else. They said it was compelling. Really? Hard to imagine that after all these years of feeling like a failure with the project--this felt like recognition.

Just because a work is unfinished, it doesn’t mean it cannot be brought back to life, with new ideas and a new vision.

Regina, Margot, Doug Doe and the students encouraged me to get myself back into the Flaherty-Benson project. Since I was now an experienced editor, designer, writer and director, I could do most of this work myself. I could also take a fresh look at the material and tell a new story of the project, a story where I could put the whole thing in context—in time, in reputations, in history. I could get the viewer involved with the story. I could never have made ROBERT FLAHERTY LOOK AGAIN in 1978. I was not a filmmaker then, but I am now.

I could now look at the film through the long lens of my filmmaking experience and ask what happened to this project?

I could say that this project has formed a bookend to my career—but that’s a cliché, really. I’m not planning on ending my film career with the Flaherty-Benson project, as I have many films I still want to create. It was the first film in my career, but hopefully not my last. However, now as I write this at the age of 68, I’m ready to stop dragging cases of camera gear in and out of elevators and double-parked cars. I’m ready to move on.